About

The Invisible Girls research programme aims to raise the visibility and voices of child domestic workers. This programme is designed to generate intervention-focused evidence to guide programming and policies that reduce the number of girls entering domestic work and promote a brighter future for current child domestic workers.

The Gender, Violence & Health Centre (GVHC) at LSHTM, are working closely with the Millby Foundation and international and local partners in South-East Asia, to develop truly feasible and affordable responses to support girls in domestic work.

Intervention Development Research

The Invisible Girls research programme is laser-focused on developing effective interventions by generating intervention-specific evidence. By using Intervention Development Research methods, we’ve moved beyond seeking evidence solely to document and call attention to problems, and instead we produce targeted data to guide what can be done by whom and in what ways it should be done to be effective.

The Invisible Girls research portfolio consists of a wide range of activities to develop the evidence-base on child domestic work, including evidence synthesis, scoping and mapping work, secondary data analyses, measurement tools and conceptual frameworks to inform effective interventions and advance scholarship.

Child domestic work

Global estimates suggest that 17.2 million children are engaged in domestic work, most of whom are girls. Child domestic workers frequently work extremely long hours, rarely attend school and may suffer physical, verbal and sometimes sexual abuse and the mental and physical health consequences.

Despite the prevalence, there are currently few interventions to support children and adolescents who are in domestic work. We use Intervention Development Research and evaluation methods to help design and test interventions for these hard-to-reach or invisible girls.

Our aims

The Invisible Girls programme aims to reduce harm associated with child domestic work and improve the context and opportunities for working children to learn, gain skills and increase their opportunities to secure safe, healthy future lives and livelihoods. Our goals include:

- Develop an evidence base to support effective interventions to improve the health and safety and future life prospects for child domestic workers.

- Increase the number of child domestic workers engaging in effective interventions that promote a safe and healthy future.

- Shift the social contract for child domestic work to improve the perception and treatment of child domestic workers.

- Instigate greater research and scholarship on child domestic work.

- Facilitate collaboration between organisations to meet the health, learning and protection needs of children in domestic work.

- Promote targeted funding, improved policies and programming that focus specifically on the needs of child domestic work.

The Invisible Girls programme is generously supported by the Millby Foundation which is dedicated to reducing violence against women and girls in Southeast Asia.

Professor Cathy Zimmerman leads the Invisible Girls programme under the Millby Foundation Research Programme on violence against women and girls in Southeast Asia. She is co-founder of the Gender Violence & Health Centre at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and her research focusses on child domestic workers, human trafficking, exploitation and gender-based violence. She is the author of the World Health Organization’s WHO Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women and Caring for Trafficked Persons: Guidance for Health Providers by the International Organization for Migration and LSHTM.

Meghna Ranganathan is an Assistant Professor of Social Epidemiology at LSHTM and is a co-investigator of the Invisible Girls programme. In this role she is responsible for co-leading and developing the programme of research that informs intervention development, in partnership with colleagues in Myanmar. She has conducted both quantitative and qualitative research exploring the linkages between social protection interventions, such as cash transfers and the impacts on sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence in low and middle-income countries. She is a Global Steering Committee member of the World Health Organisation’s Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA), and is affiliated with the Gender Violence Health Centre at LSHTM and the cash transfers and intimate partner violence (IPV) collaborative, a multi-disciplinary international group of researchers focused on evaluating the gendered impacts of social safety net programmes.

Ligia originally trained in social sciences and anthropology, with a MPhil and PhD on Preventive Medicine. Her work includes research and intervention evaluation in Latin America, Asia and Africa, with a focus on trafficking in persons, violence, and migration and health.

Aye Myat Thi

Co-investigator, Myanmar

Aye Myat Thi is a medical doctor with training in public health, with an MBBS in Myanmar and MPH from the University of Auckland in New Zealand. She was a programme manager for the community based MDR-TB project in Myanmar leading the scale up of community based TB and HIV care projects. She has been involved in operational research projects conducted by the Union and National TB/AIDS Control programs. She served as a programme coordinator for TB-malnutrition inpatient study, a collaborative project between San Lazaro Hospital, Manila, the Philippines and Nagasaki University, Japan. In her current role as a Senior Research Associate at Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) Myanmar, she is a co-investigator, Myanmar, of the Invisible Girls research programme which aims to generate evidence base to improve future and livelihood of child domestic workers.

Nicola is a mixed methods research consultant and honorary faculty at LSHTM. Her research interests are in measurement of child exploitation and health, including child labour, child domestic work and migrant labour exploitation, and interventions and policy responses to these issues. She oversaw development of the Hazardous Work module in the ILO's Child Labour model questionnaire used by National Statistics Offices to enumerate working children, and was technical lead for ILO Ethical Guidelines for Research on Child Labour.

Research

- Measurement of child domestic work and child labour

-

Measuring child domestic work can be challenging, especially in general household surveys. Child domestic workers may be misidentified as ‘fostered’ or overlooked as workers.

What do we know about the prevalence of child domestic workers?

- Globally, there were an estimated 17.2 million child domestic workers in 2012, two thirds of which were girls

- Over 20% of all child domestic workers were estimated to be in hazardous work

- There are an estimated 11,371 child domestic workers in Myanmar

- Child domestic work was the fifth most common profession among girls working in urban areas in Myanmar

Why is it difficult to estimate the number of child domestic workers in Myanmar based on the Labour Force, Child Labour & School to Work Transition Survey (LF-CL-SWTS)?

- Working children, including child domestic workers, were likely to be undercounted based on the 2014 census in Myanmar

- Only conventional households were sampled, so children from institutions (orphanages, monastic schools) were excluded

- Only 15-17 year olds were included in child domestic work estimates, and it is unclear how domestic work estimates were applied to 5-14 year olds

- The definition and categorisation of ‘domestic services’ was not well defined as part of the survey

- There is no legal framework to classify hazardous child labour in Myanmar, so estimates on hazardous labour remain uncertain

How can Myanmar improve prevalence estimates for child domestic workers?

- Use a pilot survey recognising the limitations in current LF-CL-STWS surveys and likelihood that child domestic workers are undercounted

- Following an adjustment factor exercise, three recommendations to the Central Statistical Organization in Myanmar could be considered:

- The refined, probing module could be inserted in subsequent Labour Force Surveys (LFS), after testing the minimum questions needed to obtain accurate estimates

- The refined, probing module could be inserted as a supplement in the LFS every 3-4 years

- Periodic independent surveys, like the pilot survey, could be implemented, to calculate adjustment factors that can be applied to LFS data as currently collected

- A pilot survey could be conducted near the time of the next full round of LFS surveys to ensure maximum relevance in terms of child domestic worker characteristics

- A refined child domestic worker survey module could also be included in future rounds of the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) or the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), as potential useful sources of information focussed on risks faced by child domestic workers and their health needs

Our briefing note and corresponding journal article describe current prevalence estimates for selected Southeast Asian countries, highlight questions used to ascertain prevalence and note current instrument limitations.

- Framework for child domestic work interventions

-

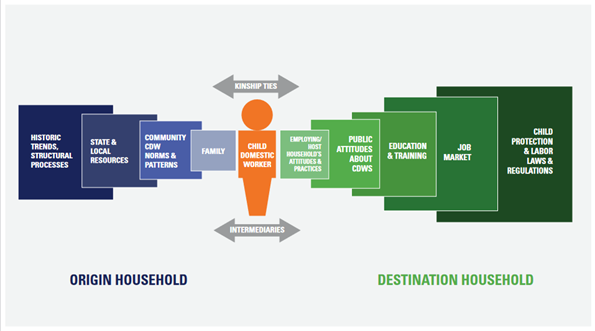

Child domestic work is a complex social phenomenon. Interventions to support youth in domestic work require multi-faceted interventions that recognise the various social and structural influences. Important considerations when undertaking coordinated action to improve the current conditions and future life prospects of children in domestic work include addressing multiple components of the social ecology of child domestic work.

Historical practices, community norms and public attitudes: Historical local practices generally set the standards for current social norms and public attitudes on child domestic work. How society views the role of children in domestic work and the obligations of the employers or host households determines the treatment of young workers. Shifting public beliefs about the social contract between young workers and host households can create substantial social pressure for hosts or employers to improve young people’s working conditions and encourage educational or skills opportunities.

Child labour and child protection instruments, laws and regulations: Laws and regulations are the scaffolding upon which these types of interventions are built. However, while it is tempting to prevent child domestic work by enforcing strict laws against child labour, it is also important not to punish poor families by removing a relatively safe coping strategy or pull youth out of situations that may be better, safer than their original circumstances. When considering policy and legislative interventions, careful planning must take place to prevent inadvertent harm that strict – or weak – regulations might create.

Kinship ties and labour intermediaries: ‘Kinship ties’ and ‘labour intermediaries’ are common links that facilitate the placement of a young person with a host or employing household. These informal or formal brokers generally negotiate placements that adhere to the socially accepted power dynamics in which youth are considered fortunate to have these positions and hosts determine the young person’s terms and conditions. If encouraged to broker better arrangements, these individuals are in a very good position to negotiate better agreements that, for example, ensure youth attend school or vocational training programmes, undertake safe, age-appropriate tasks during reasonable hours, and are encouraged to socialise with other young people.

Labour market conditions: Interventions to improve young people’s vocational skills and job-readiness will rely on evidence on locally viable future income opportunities, trades or occupations that are safe, and sufficiently well-paid. It is of little use to train young people in skills that will not generate a liveable income or will lead them into hazardous work. Youth will also benefit from support for self-confidence-building, understanding of their rights and laws and guidance on financial literacy. Given the dominance of the informal labour market in low income settings, youth will benefit from activities that increase their financial management, entrepreneurial skills, as well as their confidence and decision-making skills. Gender equity and girls’ empowerment will be especially important to address the widespread disempowerment of girls in child domestic work.

School, vocational training and life skills programming: Whether youth in domestic work go to school or engage in vocational training or other skill-building activities is influenced by: i) local customs of child domestic workers attending school; which will influence whether ii) host households permit youth the time to participate; which depends on whether iii) there are available programs that suit the availability and learning levels of the young person. Interventions for young workers must be suited to their learning levels, educational and skills needs and, importantly, their work circumstances and demands and restrictions of the host household.

Employing or host households: A child domestic worker may have kinship ties to the host household, where the host sees their role as assisting poorer relatives. Or, hosts may be employers with a more formal worker-employee arrangement. In either case, the social contract between the young worker and host commonly adheres to the community norms. Intervening with host households will work more effectively if accompanied by efforts to shift wider beliefs on child domestic work towards those that consider it ‘normal’ for young workers to go to school or vocational training or take part in life-skills interventions. Strategies to negotiate with hosts are often necessary to youth’s participation in educational or other interventions.Our briefing note goes into further detail on how this complexity framework can be used to develop effective interventions for child domestic workers.

- Evaluations of interventions for child domestic work

-

Children in domestic work are frequently isolated and cut off from education, social life and assistance options. Yet, to date, there has been little evidence about the effectiveness of activities that might support their education, skills training, and health.

What interventions have been specifically targeted for child domestic workers?

Despite the prevalence of children in domestic work and reports of harmful circumstances, there have been disappointingly few interventions - and even fewer high quality evaluations of interventions - designed specifically for child domestic workers.

A recent review of interventions for child domestic workers identified only eight evaluations of five distinct intervention programmes and only one specifically targeted child domestic workers. These interventions aimed to improve health, education or financial conditions and were conducted in Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, and Malawi. While these studies provided important findings about children in risk situations, only two interventions disaggregated child domestic workers from other youth participants.

No evaluations of host/employer-related interventions were identified.

What outcomes have resulted from interventions targeted to child domestic workers?

Health-related, education-related and economic outcomes were evaluated. Intervention results were mixed, but several studies showed reductions in depression and trauma symptoms, greater HIV knowledge, better health service utilisation and improvements in girls' literacy and numeracy.

What considerations are needed when designing future inventions to improve working conditions for child domestic workers?

Interventions for child domestic workers must be based on their specific needs and activities must be amenable to suit their availability. For example, as child domestic workers’ time and availability are generally under the control of their hosts/employers, most interventions will have to include a component to negotiate with the host/employer. There are also likely to be differences in health and social support needs between children who are living with their own parents versus children who have migrated away from home. Additionally, in literature on child domestic work, loss of education opportunities is often cited as a critical problem and hindrance to future life opportunities. Improving access to education or skills-building (occupational and soft skills) are important aspects of any intervention.

To date, there is scant evidence on host/employer-focused interventions, which makes it difficult to know how these types of interventions might operate independently or in tandem with youth-focused activities. At present, it seems that there is very little research to inform interventions, for example, by learning how hosts/employers or children themselves view the educational opportunities for young workers or options for enhancing their future livelihoods.

Evidence about costs or cost effectiveness of any interventions for children working as domestic workers will also be crucial to future investments in various intervention designs.

Importantly, any interventions need to be accompanied by strong intervention-focused research and evaluation to understand what works to improve health, well-being and educational outcomes for child domestic workers, especially what girls and young women want to help them make their own choices about their future.

What regulations should accompany future interventions designed to support child domestic workers?

There is a need for a strong policy or legislative foundation to support to accompany interventions. However, measures to immediately eradicate child domestic work are not recommended – not least because it might mean that girls move into situations that are more hazardous. That said, regulations should be targeted at improving working conditions, including limitations to working hours so young workers can participate in education or skills building and have leisure time, fair wages, and decent treatment to protect their physical and mental health.

Our briefing note and journal article offer the results of our systematic review of published literature on evaluations of interventions for child domestic workers.

- Child domestic work, violence and health

-

Child domestic workers can be at particular risk of various health, safety and child development problems, such as occupational hazards, long work hours, verbal harassment, physical abuse and, in some cases, sexual abuse.

What are the rates of violence for child domestic workers?

Our systematic review suggested that, on average, children worked between nine and 15 hours per day with no rest. Child domestic workers’ exposure to violence varies substantially by country and context. Median rates of abuse for child domestic workers ages 5-17 were:

- 56% experienced emotional violence

- 19% experienced physical violence

- 2% experienced sexual violence

Reported work-related injury and illness ranged from 7%-68%, and up to half did not receive medical treatment. Injuries included cuts, slashes, electrical shocks, falling from stairs, and sore fingers and toes from detergent use.

How does abuse impact child domestic workers?

The prevalence of reported emotional abuse greatly influences children’s mental health. For child domestic workers, the absence of caregiving compounded by psychologically abusive treatment can lead to long-lasting damage to a child’s healthy development and wellbeing. Harmful working conditions, including long hours and restricted freedom of movement further increase the likelihood of poor health outcomes, including mental health problems and cardiovascular diseases.

Findings from our rapid systematic review on outcomes associated with child domestic work aim to guide potential interventions to support the health and well-being of children in domestic work. Results are summarized in our briefing note and journal article.

- Public attitudes on child domestic work

-

Reports from around the world indicate that the conditions of child domestic work are heavily influenced by local cultural and social norms. Moreover, harmful circumstances for young workers don’t tend to change until harsh treatment becomes socially unacceptable, and families wish to avoid community disapproval. To examine the potential to shift attitudes, we conducted a household survey to explore current perceptions about child domestic work in Myanmar.

How was the survey conducted?

We conducted a phone survey of 1,072 participants between 18-60 years-old from middle- and upper-class households in Yangon and Mandalay urban townships. The study was designed to learn how the Burmese public, and in particular, hosts/employers of child domestic workers, think about child domestic work.

What are the survey findings?

Findings indicate that child domestic work is common, as 84% of individuals know one or more households who have had a live-in child domestic worker. Results also suggest many individuals (40%) thought child domestic work was not good for young people, and most (75%) believed that interventions, such as vocational training, would be of benefit. These types of skills-building opportunities seemed to be acceptable if they were delivered at convenient times and locations.

What are the next steps?

These findings are intended to inform our public information activities to improve the ‘social contract’ between young workers and host households around the treatment and living and working conditions of child domestic workers.

Shifting public beliefs about this social contract have the potential to increase social pressure among hosts or employers to improve young people’s working conditions and encourage educational or skills opportunities.

A briefing note and publication of our findings will follow shortly.

- Host and employing households’ perceptions of child domestic work

-

Host households and employers of child domestic workers set children’s work conditions, which determine their health, safety and well-being.

How do host and employing households recruit and pay child domestic workers?

The majority of hosts/employers explained they recruited child domestic workers through friends, relatives, or connections with previous domestic workers. Only a minority use a broker or agency.

Child domestic workers were paid between $33-$100USD per month, with some receiving school fees or food and accommodation in place of a salary.

What do host and employing households want from child domestic workers?

Hosts/employers expected child domestic workers to have basic skills in domestic chores, such as cooking and household chores, good manners and communication, literacy skills, and childcare skills. Several noted that it was important that domestic workers could keep private family issues confidential, be obedient, not talkative, and show initiative. Several also mentioned they wanted workers to have good personal hygiene.

What are the challenges of hosting or employing children to carry out domestic work?

According to hosts/employers, the main challenges of having children as domestic workers include home security, laziness, or reluctance to do routine tasks, ignoring hosts’/employers’ instructions, leaving their job without giving notice, dishonesty, including theft and not admitting mistakes, and they also discussed health concerns, such as head lice, scabies, or bed wetting.

Importantly, because hosts/employers were supervising and accommodating children in their homes, they felt responsible to act as the guardian for their child worker, which complicated employer-worker relationships.

What types of services or training for child domestic workers would be desirable to employers?

When asked whether they would permit their domestic workers to participate in external training or education, some agreed it would be feasible if:

- The worker was over 20 years old and interested in the training or education activity

- The worker’s hours did not overlap with busy times in the house

- The classes were easily accessible, ideally free and located close to or in the employer’s home, or online

- Courses were facilitated by a mentor

Hosts/employers also emphasised that the organisations delivering education or training services must be responsible for the safety and wellbeing of the young participants, and accountable to the child’s household.

Our briefing note and corresponding scoping report further detail how hosts/employers view their household helpers and their perceptions of the challenges, benefits and responsibilities of employing young people and hosts'/employers’ opinions about potential interventions to support girls’ education, vocational training and life skills support.

- Research with brokers and former child domestic workers

-

We carried out qualitative interviews with labour intermediaries (n=16) and former child domestic workers (n=11) to learn how to shift host-family beliefs about their role as guardians and to identify safe ways to engage with children in domestic work.

How are children recruited and placed into host households by brokers?

The brokering practice is primarily trust-based and informal, relying on kinship and friendship networks. Intermediaries generally work alone or with other senior brokers, mostly relying on their widespread community connections in both destination and sending regions. Online recruitment is generally regarded as unreliable.

What responsibilities do brokers believe they have for the children they place?

Several intermediaries stated they felt responsible for placing girls in safe homes and some noted that they step in when there are problems, often when the employer complains (e.g., ‘child is lazy’, homesick, or physical abuse). However, there is currently little to no empirical evidence on how intermediaries organise placements or whether they advocate terms and conditions that favour the well-being of the child.

Do brokers encourage educational or skills training opportunities at host households?

Individuals who broker the arrangements for workers noted that they never try to negotiate for the child to remain in school.

However, intermediaries may be in a good position to negotiate age-appropriate terms and conditions with host / employing households, for example, to ensure youth attend school or vocational training programmes and, if working, undertake safe, age-appropriate tasks during reasonable hours. Intermediaries might also be encouraged to promote time off for young workers to socialise with other young people and have time to study or relax.

Did host households encourage educational or skills training opportunities for their former child domestic workers?

Several former child domestic workers reported they attended school while working. This is an important finding because it tells us that going to school while working is a viable circumstance that can be promoted with hosts/employers. However, at the same time, interventions for young workers must be suited to their learning levels, educational and skills needs and, importantly, their work circumstances and demands and restrictions of the host household.

What were the experiences of former child domestic workers who were able to attend school?

Young workers who went to school explained that they were teased and felt stigmatised because they were child domestic workers. These results highlight that interventions to include young workers in school will require components to reduce discrimination by other school children and strategies to promote self-confidence and decision-making among young workers, especially among young female workers.

How will these insights from former child domestic works help shape future interventions?

Interviews with former child domestic workers aimed to inform direct interventions to support CDWs. Questions were designed to identify the safest, most effective ways to access and engage young workers. Discussions explored what young people believed would be useful to improve their current circumstances and their future life prospects.

A briefing note and publication of our findings will follow shortly.

Methods

- Intervention Development Research

-

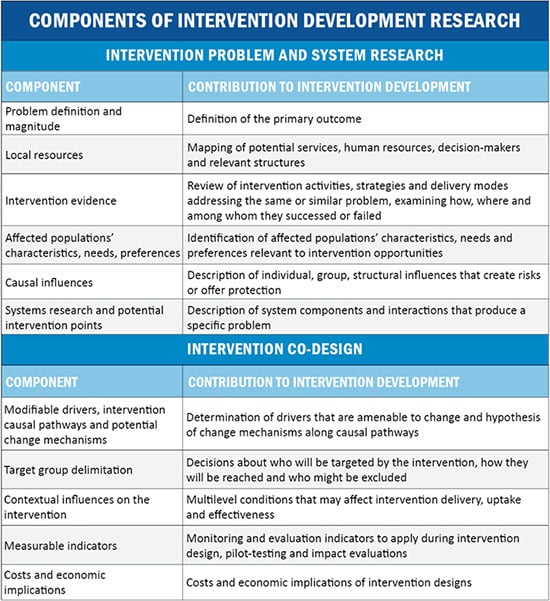

The Invisible Girls research programme is developing cutting edge Intervention Development Research (IDR) methods to generate intervention-specific evidence. This means that we’ve moved beyond seeking evidence solely to document and call attention to problems, and instead we produce targeted data to guide what can be done by whom and in what ways it should be done to be effective.

IDR methods comprise the R&D phase to find solutions for complex social problems. They focus on what is needed to develop context- and population-relevant activities and take account of the dynamic and interactive nature of complex systems. Importantly, IDR methods also recognise the centrality of participation and co-production to produce population-informed intervention prototypes.

For our research, we developed and advanced specific IDR components for intervention-centred methods, as seen in the table below, which draw on a small body of literature on intervention development principles. This framework is designed to guide data collection and analysis and inform decisions on intervention delivery, uptake and effectiveness, while also accounting for their interdependence and the potential effects of contextual influences.

These methodological steps have been shared with others to use on similarly complex social problems, such as human trafficking, child labour and sexual abuse, that require similarly complex social interventions.

A briefing note and publication on these methods will follow shortly.

- Intervention resource mapping

-

Given the limited interventions currently focused on child domestic work globally and the absence of services in Myanmar, we mapped local referral resources to support the safe conduct of research with youth, ascertain potential intervention partners for intervention development and to start to build an advocacy network.

Our briefing note and corresponding report describe the variety of services that are potentially suited to meet the various needs of child domestic workers in Myanmar.

- Ethical and safeguarding guidance for co-produced research with youth on youth in risk situations

-

While there has been a growing body of guidance for ethical research with youth, to date, there has been little to no research to test and evaluate guidance specifically for research about young people in risk situations that is co-produced with youth. This project aims to develop and test an ethical and safeguarding protocol for research with youth in risk situations in multiple regions.

This work is associated with The British Academy Youth Futures programme.

The Invisible Girls research programme aims to raise the visibility and voices of child domestic workers. We do this by generating intervention-specific evidence to inform effective strategies to promote the safety and life prospects of young women and girls in Southeast Asia. Our work draws on strategic collaboration, which means seizing opportunities to collaborate with influential groups, including child domestic workers, host families and local and international organisations. Simultaneously, we respond to the evidence needs of initiatives working to benefit young women and girls.

Achieving a ripple effect

In our work, we achieve a ‘ripple effect’ by providing robust evidence where it can have the greatest effect. We have built strong linkages with influential international and local partners. We regularly aim to ‘punch above our weight’ by collaborating in ways that will catalyse change via organisations with greater resources and farther reach. We work with the most influential individuals, the people in the communities where changes are meant to occur.

Our impact

Our work has influenced how research is conducted to find solutions for complex social problems. Specifically, our intervention-focused methods on child domestic work in Myanmar have encouraged donors to fund intervention-centred approaches and helped others apply these methods for their research on, for example, human trafficking, child labour and sexual abuse.

Find further examples of our impact below.

- Established foundational evidence to develop targeted interventions to improve the lives and livelihoods of child domestic workers

-

Among the most substantial aims of our current research is to generate the body of evidence required to develop well-targeted and effective interventions to support the health, well-being and future livelihoods of children in domestic work. Our current findings are supporting the development of two core intervention components:

- Targeted campaigns to shift the public and host-family beliefs about the social contract for child domestic work; and

- A combined economic and social intervention model to reach children in domestic work

- Provided the first-ever global evidence-base on interventions that support child domestic workers to guide program and funding decisions

-

Findings from our systematic review provide the first evidence on interventions that have been evaluated to support children in domestic work and to inform future programming and policy-making. Results indicate that interventions have attempted to improve the health, financial literacy and education of child domestic workers. However, there is currently very limited rigorous findings about ‘what works’ to foster a promising future for child domestic workers.

- Improved the global measurement of the health and safety of working children

-

Our work resulted in two new survey modules for the International Labour Organization’s international child labour surveys (SIMPOC) – the most important global surveys on child labour. These two new modules will be used in all future national surveys on child labour: i) Occupational Health and Safety; and ii) Violence.

This change ensures that the occupational hazards of child domestic workers will be identified with a specific module: Part E. Unpaid household services in the own household (household chores). We were also able to ensure questions about violence were posed in ethical and age-appropriate ways.

- Increased attention and funding to child domestic work

-

Based on our research and international engagement, the Invisible Girls programme has raised the profile of child domestic work with key donors, including the US government, which launched several funding calls focused on child domestic work. To date, the State Department is supporting research and interventions on child domestic work in Morocco, Ethiopia, Liberia and Nigeria.

- Galvanised Freedom Fund to launch their dedicated programme on child domestic work

-

We began our Invisible Girls programme by collaborating with the Freedom Fund, which has motivated the Freedom Fund to establish their own programme and dedicated funding to address child domestic work. We remain a partner and have an advisory role on their current work in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Liberia, sharing research findings, programming ideas and intervention plans.

- Stimulated and co-developed the ILO’s new ethical guidance for surveys on child labour (SIMPOC) that will be used by National Statistics Offices globally

-

Based on the work we undertook for the International Labour Organization’s international child labour survey (SIMPOC), we worked with the ILO team in Geneva to identify a need for ethical guidance for their survey on child labour. Following discussions, the ILO issued a call for proposals to research and draft this guidance document and a call for Ethical Guidance for their global survey on Human Trafficking and Forced Labour. Dr. Kyegombe and Prof Zimmerman were advisors for each of these projects with Samuel Hall Research Group.

- Increased attention to the health implications of child labour

-

Our analysis of UNICEF data identified the relationship between hazard levels in child labour and mental health, social outcomes and school drop-out rates, which will increase attention to the health protection and service needs of children in domestic work. For our future interventions and for policy-makers, finding that the more hours a child works, the greater the risk to psychosocial well-being and likelihood of very poor educational attainment, can provide evidence for more stringent regulations, specifically for children in domestic work.

- Improving research methods to design intervention prototypes for overlooked populations and under-developed intervention areas

-

Our research for the Invisible Girls programme is advancing Intervention Development Research (IDR) methods, which are intended to generate intervention-focused evidence that can be used to design intervention prototypes for pilot testing. These methods have been shared with, for example, the US State Department Trafficking In Persons (TIP) programme, the US Department of Labor, the International Labour Organisation and the University of Malaya. Additionally, they have been used to guide the 2023 US State Department’s Notice of Funding Opportunity on human trafficking.

- Macro-economic analysis of the 'whole-economy' costs of child domestic work

-

We are working with Dr. Tarp-Jensen, Dr. Keogh-Brown and Innovations for Poverty Action to develop questions for employer interviews that will inform the economic analysis of the ‘whole-economy’ costs of child domestic work in Myanmar. This analysis will be based on a recently completed project with the UN University, which resulted in a paper, Labour market projections and time allocation in Myanmar: Application of a new computable general equilibrium (CGE) model. Analysis on child domestic workers will draw on the data generated by the employer interviews and attitudes survey. The results will be used both as specific evidence for Myanmar and, importantly, as a methodological prototype for others to build economic models on child domestic work in their contexts.

Publications and briefing notes

Link to publications and briefing notes

Conference presentations and keynote lectures

Aye Thiri Kyaw (2022). Generating Evidence to Support the Elimination of Child Labour, Forced Labour and Human Trafficking conference: Opening the “black box” of protection and reintegration interventions for trafficking survivors in Myanmar: A realist focused evaluation of World Vision’s Anti-trafficking in Persons (A/TIP) program

Nicola Pocock (2022). Generating Evidence to Support the Elimination of Child Labour, Forced Labour and Human Trafficking conference: Providing conceptually grounded insights on modifiable determinants of trafficking-related outcomes to inform a counter-trafficking Behaviour Change Campaign in Haiti.

Cathy Zimmerman (2022). Human Trafficking Research to Action (RTA) conference: Intervention Development Science: Do we need it? What would it do?

Nurturing the next generation of scholars on violence against women and girls in Southeast Asia.

Measuring harmful vs beneficial child domestic work: Aye Thiri Kyaw

Thiri is a Millby-Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA) scholar, also supported by fee reductions from LSHTM. Thiri’s work will be pivotal to the ways that child domestic work is perceived and measured. She is applying sophisticated methods, Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis, to develop tools to measure the levels of harm (or benefits) associated with different conditions of child domestic work. Her Ph.D. thesis will define the different dimensions of child domestic workers’ working conditions that affect their health and well-being in Myanmar and determine the conditions that are ‘necessary and sufficient’ to a harmful or beneficial outcome. Ultimately, findings will inform measurement approaches for future surveys and interventions for child domestic workers.

Exploring the well-being of adolescent girls in Myanmar in collaboration with Girl Determined: Isabelle Pearson

Isabelle is working collaboratively with young female peer researchers from Girl Determined (GD), a local NGO in Myanmar. Her research is highly participatory, working in collaboration with young female peer-researchers from GD to explore how adolescent girls view their well-being as well as the current risks to their well-being. She is working closely with GD to help Brooke and team identify how the programme is supporting young women under these especially constrained circumstances and identifying areas for programme development. To date, Isabelle and her team of peer researchers have conducted 12 focus group discussions with 72 girls aged 12-18 years across urban and rural settings in Yangon and Mandalay. Participants are mostly from the lowest socio-economic quintile, from a wide range of backgrounds including girls who have been sent to boarding school to flee the conflict in their home states, young Buddhist nuns and girls inside and outside of formal education. Findings will be used to inform a survey tool to measure well-being and its associated risk and protective factors among a sample of 750 adolescent girls.

Isabelle’s research has implications for local intervention programming, and support for girls in other unstable, conflict-affected settings. Additionally, her study will contribute academically to future measurement of ‘well-being’ among girls in conflict-affected risk situations, and methodologically, to safeguarding approaches for peer-research with girls in risk contexts.

Rohingya refugee girls in Malaysia: Zhen Ling (Alyson) Ong

Awarded the ESRC-UBEL scholarship, Zhen Ling (who goes by Alyson) will focus her PhD work on adolescent Rohingya refugees in Malaysia to consider their health, safety, and well-being under the restrictive Malaysian regulations for migrants.

Alyson is working in close collaboration with the Rohingya Women’s Development Network and HOST International to research ‘safe spaces’ for Rohingya adolescents. Although the second largest Rohingya population in Malaysia, they are rarely recognised in international dialogue and not recognised by Malaysian law or services. Among the most prominent risks for Rohingya girls is very early marriage (e.g, age 12-14). Alyson’s research focuses on the co-production with Rohingya girls of their definition of safety and what, for them, would comprise a safe space. As part of this work, Alyson and her local partners will be providing training and tailored information to help the girls consider different aspects of safety from violence, psychological well-being, bodily autonomy, and menstrual health. We intend to build on Alyson’s foundational work by developing a full programme of intervention development research for Rohingya girls.