NHS 70 series - The creation of the NHS

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine https://lshtm.ac.uk/themes/custom/lshtm/images/lshtm-logo-black.png Thursday 14 June 2018NHS at 70 – if original ideals are to be sustained then we need honesty on its running costs

The National Health Service (NHS), which turns 70 next month (5 July 2018), characterises a particular type of health system. One which is universal, covering all citizens; comprehensive, providing a full range of services ‘from cradle to grave’; and free at the point of use, with funding coming mostly from general taxation. In 2018, debate rages over how far these three cardinal principles still remain. Arguably, sustained austerity in health and social care funding has undermined comprehensiveness, while the recent experiences of the Windrush generation demonstrate the limits of universalism. With much talk today of whether the NHS can survive, it is helpful to remind ourselves why it was created back in 1948.

First, it’s important to bust a few myths. The NHS did not arise from a crisis of existing health services, or because population health had drastically worsened, or because of a public outcry. In comparative terms, interwar Britain had a rich variety of provision, ranging from the voluntary hospitals which delivered acute care, to local government public health services, which addressed infectious, psychiatric and chronic diseases, to residual Poor Law institutions, whose remit covered both health and social care. Ratios of GPs to population were good, and working-class wage earners were covered by National Health Insurance (NHI), introduced in 1911. The Depression had certainly exposed grievous health inequalities, but on balance mortality indicators were improving, thanks in part to the budding welfare state. And public opinion data from the late 1930s and early 1940s suggest most people were broadly satisfied.

Why then did a major reform occur? During the 1930s, a debate brewed amongst doctors, civil servants, medical academics and local government officials, about how to improve the system - problems lay with gaps, patchiness and unfairness. Only about half of the population was included in NHI, leaving children, homemakers, older people and the middle class without cover. They faced fees for GP visits, means-tested charges for voluntary hospitals, or separate insurance through ‘contributory schemes’. GPs tended to devote more time to richer paying customers, which upset the NHI patients. Meanwhile, accessing free services through the Poor Law still carried some stigma and humiliation. Geographical inequities, caused by the ‘caprice of charity’ and the unevenness of local taxation, were another flaw.

These concerns escalated into momentum for change during World War Two. An Emergency Medical Service co-ordinated by central government provided a model for what a properly integrated NHS might look like. Then in 1942, the Beveridge Report was published with its blueprint for a post-war welfare state that inspired the war-weary British. Public opinion and the political centre ground shifted in favour of a universal, comprehensive service, though the optimal administrative structure was hotly contested, not least by the British Medical Association, whose members dreaded becoming public employees.

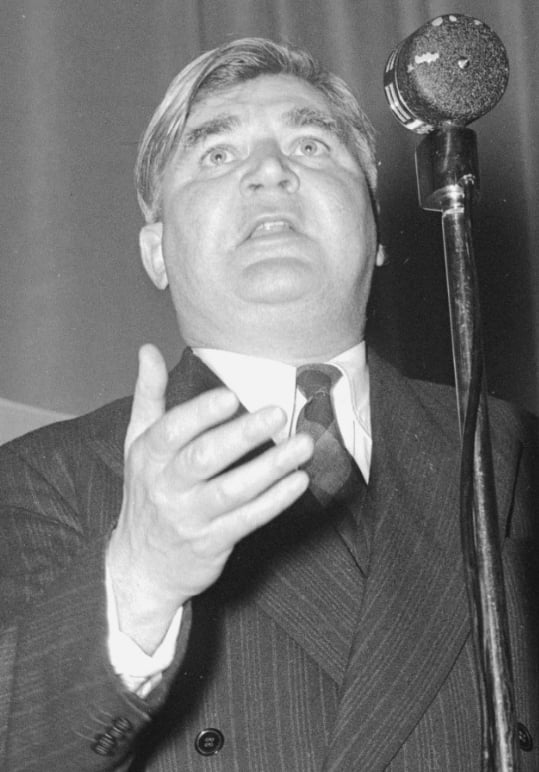

The 1945 election broke the stalemate with a new, decisive minister of health, Labour’s Aneurin Bevan, who was willing to confront interest groups and pursue redistributive policies. A universal NHS was launched, funded by progressive general taxation, with no up-front charges. Hospitals were ‘nationalised’ and grouped under new NHS boards. GPs remained self-employed, but contracted for NHS work, while hospital doctors became handsomely paid salaried employees.

Bevan’s creation was not without design flaws, in particular its vulnerability to underfunding by governments bent on curbing public expenditure, notably Conservative administrations of the 1950s, 1980s and 2010s. Nonetheless by all international comparisons, Britain’s planned, integrated system has proven extremely successful at promoting equity, efficiency and cost-effectiveness. There is no good evidence that abandoning a tax-based system would be more ‘sustainable’, but politicians do need to level with the public about its costs, if the original ideals are to be sustained.

This expert opinion piece is part of a series that LSHTM are publishing in the lead up to the 70th anniversary of the NHS on 5 July 2018. You can read more about our NHS 70 series and join the conversation online using #NHS70LSHTM.

LSHTM's short courses provide opportunities to study specialised topics across a broad range of public and global health fields. From AMR to vaccines, travel medicine to clinical trials, and modelling to malaria, refresh your skills and join one of our short courses today.