World Breastfeeding Week: Extreme heat and breastfeeding

1 August 2023 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine https://lshtm.ac.uk/themes/custom/lshtm/images/lshtm-logo-black.png

Last month many people experienced severe heatwaves, with temperatures in North America, parts of Asia, and across North Africa and the Mediterranean above 40°C for a prolonged number of days. The newly declared El Nino is expected to amplify the occurrence and intensity of such extreme heat events this year. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) states that these heatwave events have increased sixfold since the 1980s and calls for more investment in heat health planning and early warning systems. It has become more urgent to understand how high temperatures impact maternal and child health. Although millions of women live in hot or tropical climates, the role of environmental heat as a barrier to exclusive breastfeeding is not often considered.

Exclusive breastfeeding (no food or liquid except for breastmilk) is a life-saving practice for children, who are protected against infections. While many women breastfeed their children over many months in Africa, a smaller proportion practice exclusive breastfeeding.

What is the role of heat in the practices of breastfeeding and are there specific concerns of women and providers? The Climate, Heat and Maternal and Neonatal Health in Africa (CHAMNHA) consortium includes the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Aga Khan University Kenya (AKU), the Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Sante (IRSS) and several other institutions. It has investigated the impact of heat on breastfeeding through systematic reviews and ethnographic and epidemiological studies.

Breastfeeding advice is provided by health workers, peers and family circles, and cultural beliefs can be highly influential on maternal intention to breastfeed exclusively. Healthcare providers and relatives sometimes advise that water supplementation is needed in hot weather. A systematic review of studies on infant hydration led by CHAMNHA found no evidence that infants under the age of 6 months require supplementary food or fluids in hot weather conditions. Only nine studies were found and there is a need for new research that also assess the welfare and hydration of the mother. Breastmilk quality may also change in hot weather, because of heat as well as the effect of changes in feeding routine.

CHAMNHA recently published a study investigated the impacts of heat on mothers’ breastfeeding behaviours in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Postpartum women were interviewed three times over 12 months. They told us about the activities they had carried out the previous day and the time spent on each activity. We looked at the relationships between women’s activities and temperature from the local weather station and found that women spent less time breastfeeding when it was hot, equating to 25-minutes less on the warmest compared to the coolest days of the year. For infants over 4 months old, hot weather had an even greater impact on the time spent breastfeeding. Women were less likely to exclusively breastfeed their very young infants in extreme hot weather. As temperatures increased, women provided supplementary fluids, mainly water to their very young child.

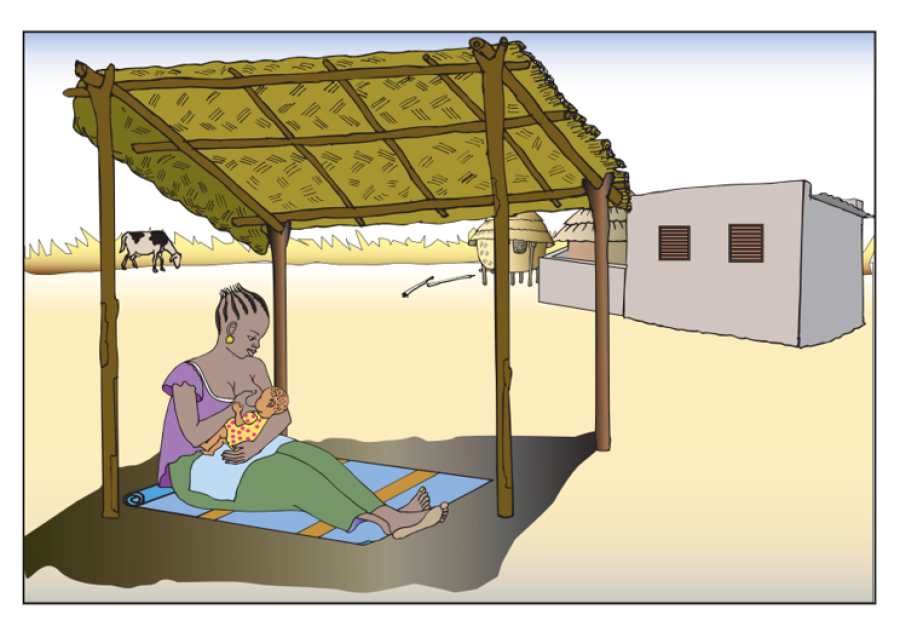

This finding is supported by interviews with mothers, family members and health workers in rural communities in Kenya and Burkina Faso that have also found that heat has a significant effect on exclusive breastfeeding. Mothers report that high temperatures cause discomfort and increase irritability and exhaustion. Babies were reported to be too uncomfortable to sleep or to breastfeed. In Kilifi, Kenya, mothers reported that while breastfeeding in the heat, they had to remove their clothes, causing their babies to be unlatched from the breast. The impact on babies was perceived to be amplified by the indoor heat and household air pollution from cooking.

“The extreme heat affects the baby during breastfeeding, it affects the baby because she can't concentrate on breastfeeding... even breastfeeding she can't do it well… when there is more heat, the baby is uncomfortable to breastfeed as he continues to cry due to hot temperatures. It is really a problem.”

Male Spouse, Viragoni, Kaloleni, Kenya

"The child suffers from the heat as well as the mother... If you lie him down too, it's just crying. He doesn't know what to do. It's just suffering. Even to breastfeed him/her, it is difficult."

Postpartum mother, Delga, Burkina Faso

"Very often mothers want to be alone, they want to get some fresh air, so I find that babies are neglected during the heat. When it's hot, the mother herself is not free-spirited. She doesn't want to go near her baby, because if she does, the heat increases. As a result, the desire to breastfeed with love disappears.”

Health professional, Delga, Burkina Faso

Our study in Burkina Faso also showed that higher temperatures did not reduce the amount of time women spent on household chores or informal work. These findings are echoed in the conversations with women in Kilifi, who report that their workload is not reduced during high temperatures and in some cases is increased because tasks take more time, for example, women must walk farther to fetch water. This can mean there is less time for childcare or breastfeeding.

Access to cooling and shading should be for everyone. Temperatures can increase locally due to deforestation and poor urban design. Understanding how housing quality influences neonatal health, especially in hot low-resourced settings, is crucial. In many parts of Africa, people live in small, poorly ventilated houses without windows and with roofs made of heat-trapping materials. Adapting building materials to counteract rising ambient temperatures is important as well as increasing access to reliable electricity which will reduce individual exposures to high temperatures.

Our research clearly shows more needs to be done to discourage water or other fluid supplementation when breastfeeding infants below 6 months old. Families and healthcare providers can be reminded that exclusive breastfeeding is recommended even in hot conditions. Measures should be taken to ensure that mothers have adequate nutrition and are not dehydrated. Improved guidance involves healthcare providers who are critical to inform and guide pregnant and postpartum mothers and families on how to avoid dehydration and heat illness among neonates.

LSHTM's short courses provide opportunities to study specialised topics across a broad range of public and global health fields. From AMR to vaccines, travel medicine to clinical trials, and modelling to malaria, refresh your skills and join one of our short courses today.